Infrastructure of Deportations

Deportations – the forceful removal of people across nations – are facilitated by a complex network of infrastructures (e.g. buildings, harbours, airports, roads, ships and vehicles). In this blogpost, we will briefly illustrate the different phases of deportations from Lesvos to Turkey in order to point out the roles of important players who facilitate these practices of removal. We will explore a general overview to focus on the infrastructural network that facilitates deportations from Lesvos to Turkey.

Pre-Removal Centres

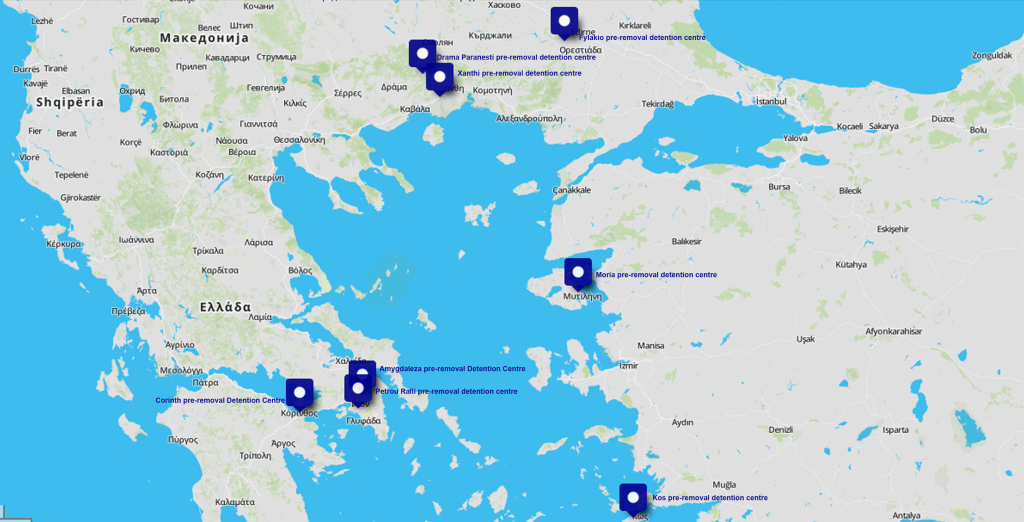

Most people who face deportation from Greece to Turkey are detained in pre-removal centres. Greece has eight pre-removal centres; Amygdaleza (Attica) Corinth (Peloponnese), Drama Paranesti (Thrace), Fylakio Orestiada (Thrace), Kos (Aegean), Moria (Lesvos) (Aegean), Tavros (Petrou Ralli) (Attica), and Xanthi (Thrace).

Moria Pre-Removal Centre

Our work mostly focusses on the situation on Lesvos. The pre-removal centre of Lesvos is located inside the Hotspot facilities of Moria Camp that became officially operational in summer 2017. However, it was already used as a detention centre since the military base became a European ‘Hotspot camp’ in 2015. The pre-removal centre is a compound surrounded by several Nato barbed wire fences. It has two main sections (section A and B) and falls under the responsibility of the Hellenic Police. Within these different sections, people are forced to live in containers where they are sometimes locked in and share the “room” with multiple people without any privacy about. The pre-removal centre has the capacity to detain 420 people.

pre-removal centre Lesvos

Some people who were released from prison reported severe police violence against detainees. Furthermore, there have been several cases of people inside Moria detention centre attempting suicide or self-harming.

Grounds for Detention in Moria Pre-Removal Centre

According to Greek law, people can be detained in pre-removal centres when they (1) display a risk of absconding (2) avoid or hamper the preparation of the return or removal process or (3) present a threat to public order or national security (Law 3386/2005, article 76(3) Law 3907/2011, article 30(1) (see Global Detention Project 2018). Currently, the majority of detainees in Moria pre-removal centre are asylum seekers with second rejection – people whose asylum claim has either been rejected or declared as inadmissible and whose appeal was rejected as well. Also imprisoned are participants of the so-called “voluntary return program” of the IOM, who have to wait for their transfer to the Greek mainland in detention. The period of detention can vary from several days to weeks up to months of detention (see AIDA)

Police Station in Mytilene

Either in the early morning or in the late afternoon the day before the scheduled deportation, people who will be deported are transferred from the pre-removal centre in Moria to the police station in the town of Mytilene where they are put into custody. They are often brought from Moria prison to the police station by a Frontex prison bus supplied by one of the EU member-states.

Since 2016, as part of their Frontex mission, the Dutch Transport and Support department of the Custodial Institutions agency (DJI) of the Ministry of Justice and Safety has been supporting Hellenic Police and the Hellenic Coast Guard. According to the annual report of 2017, published in May 2018, there were six employees and 2 prisoner support busses on Lesvos. During their work, a Greek police officers was present as a liaison officer.

Since 2016, as part of their Frontex mission, the Dutch Transport and Support department of the Custodial Institutions agency (DJI) of the Ministry of Justice and Safety has been supporting Hellenic Police and the Hellenic Coast Guard. According to the annual report of 2017, published in May 2018, there were six employees and 2 prisoner support busses on Lesvos. During their work, a Greek police officers was present as a liaison officer.

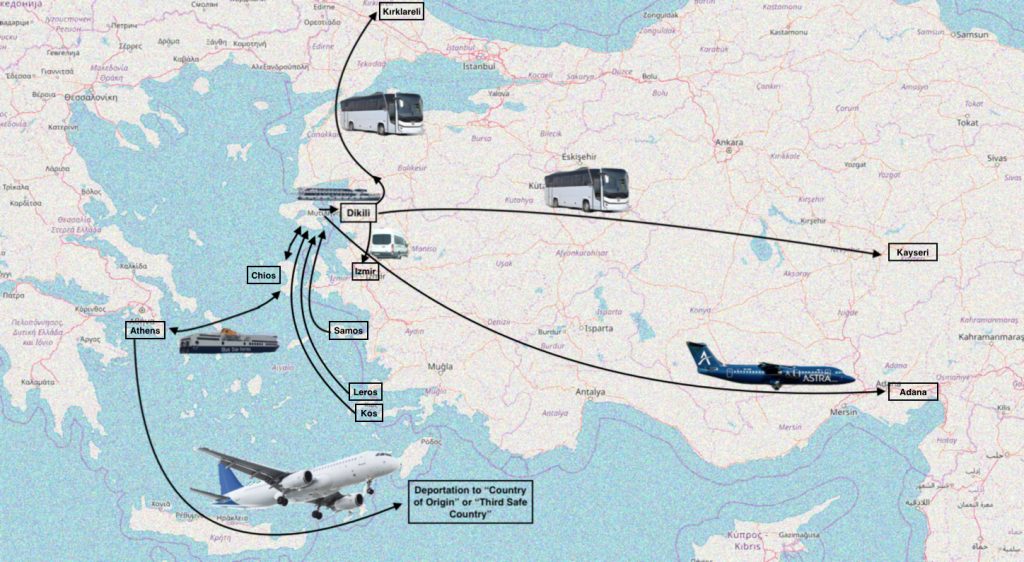

Deportees often have to stay over night – or sometimes longer, if their deportation is postponed – in custody in the police station. The police station has the capacity to detain around 20 people. From the police station, people are either brought to the airport to be deported by plane to Adana or to the port of Mytilene from where they are deported to Turkey (Dikili) or the Greek mainland. Mostly Syrians are brought to Adana while other Nationalities are deported by ferry to Dikili from where they are brought to different detention centres in Turkey. Syrians are considered as potential refugees who can get temporary protection and are brought to open camps. Non-Syrians deportees are mostly considered economic migrants and treated as such. After their deportation to Turkey they can stay in detention up until a year in Turkish detention centres.

Deportation Transfers from other Places

In some cases, people are transferred from other Greek islands such as Chios, Leros, Samos and Kos or the Greek mainland to Lesvos to be deported to Turkey. This way, Lesvos becomes a transit zone for people who are deported to Turkey. People are mostly transported by the regular passenger ferry between Athens and Lesvos. The Hellenic Police escorts and facilitates these deportations. Inside the ferry, people facing deportation are forced to stay in a room separating them from the “regular passengers”. They are handcuffed together in pairs of two, in some cases even during the entire journey which can take up to 10 hours. In some cases, people arriving on Lesvos are first transported to the Moria pre-removal centre. In other cases people are immediately transferred to another ferry to Turkey after their arrival on Lesvos.

Deportations to Dikili (Turkey)

The deportees who are detained in the police station awaiting their deportation to Turkey are handed over to Frontex officers by the Hellenic Police. With a green coach, rented from a commercial Greek tourist company, Frontex transports people from the police station to the harbour of Mytilene. They use so-called “return escorts”; employees of European member states who work for Frontex to support national “escort officers” during return operations.

The deportees who are detained in the police station awaiting their deportation to Turkey are handed over to Frontex officers by the Hellenic Police. With a green coach, rented from a commercial Greek tourist company, Frontex transports people from the police station to the harbour of Mytilene. They use so-called “return escorts”; employees of European member states who work for Frontex to support national “escort officers” during return operations.

Deportation Ferries

Based on our observations, we identified three ferries that facilitate deportations to Turkey. The boats that are used for deportations are not only “deportation ferries” but are also used for regular passenger transport.

After researching Frontex and their role in the deportation process and Greek tourist companies we found out that several commercial tourist companies play a key role in facilitating deportations. Since 2018, Frontex signed several contracts with commercial tourist companies to facilitate “support to law enforcement operational activities. The services are mainly associated with the corresponding transfers by sea between 1 designated port of departure in Greece and 1 designated port of arrival in Greece/Turkey” (Frontex tender contracts 2017). Sunrise Lines E.P.E. (Ltd) has a 2-million-euro contract with Frontex to deport people from Lesvos to Dikili (Turkey). In another blog-posts we will further explore these contracts in depth.

Dikili

In Dikili, the deportees are handed over to the Turkish state officials. Frontex personnel stay on the ferry and return to Lesvos. From the harbour in Dikili, people are brought to different detention centres in Turkey. Although there are 33 detention centres in Turkey, it seems that people are mainly brought to Kayseri, Izmir or Kirklari. People are either transported by either a coach or a mini bus, funded by the European Union. The drive from Dikili Izmir takes around 1.5 hours, while the journey from Dikili to Kirklari takes around 7 hours and Dikili to Kayseri takes around 11 hours.

Adana

Syrians are mostly deported by plane to Adana from where they are transported to a refugee camp where they can in theory apply for a so-called “temporary protection status”. However, most Syrians have – according to the European Commission – only been pre-registered for temporary protection. Moreover, some preferred to “voluntarily” return to Syria instead of staying in Turkey.

Detention in Turkey

When people are deported and detained in Turkey it is extremely difficult to follow up their cases. Recent academic publication (see Alpes et al. and Ulusoy and Batjes) show important insights in what happens after deportation from Greece to Turkey under the EU-Turkey statement. Ulusoy and Batjes describe serious human rights violations in Turkey. Access to international protection is exceptional, detainees are subject to clear infringements of procedural rights and they identified several cases of arbitrary detention and the risk of deportation without juridical review.

In theory, non-Syrians can apply for a weak form of subsidiary protection. However, according to the European Commission’s last report on the Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement from September 2017, out of 1,896 people deported to Turkey, 831 non-Syrians have been deported further to their countries of origin, although only 9 people had rejected asylum claims.

detention centers in Turkey source: Global Detention Project

Summary

The above described elements that facilitate deportations can be visualized on a map.

by P.