Under the EU-Turkey Deal, people whose asylum claims have been rejected or declared as inadmissible are deported back to Turkey. While Syrians are flown to Adana, people of other nationalities are returned by ferry to Dikili, from where they are usually directly transferred to the so-called Removal Centre in Harmandalı close to İzmir. The following posts focuses on the situation in the Removal Centre Harmandalı and outlines how the EU deportation policy leads to the systematic violation of basic rights.

Harmandalı is one of 24 Removal Centres in Turkey that have the total capacity to hold 16,116 people. In the future, 13 new Removal Centres shall become operative increasing total capacity to 21,466 people.

Harmandalı has capacity for 750 people in 126 rooms. There are two blocks, A and B. In block A, mainly single male adults are held in detention, Block B holds families and children. Some migrants who were apprehended at the Turkish coast or in the Aegean Sea trying to leave Turkey are also detained in Harmandalı.

Entrance of Harmandalı Removal Centre, March 2019

Removal Centres are immigration detention centres that serve to facilitate deportations of people to their countries of origin. Lawyers reported that deportees sent back from Greece are often transported first to Harmandalı and then to other Removal Centres, from where they can be more easily deported. In the past, deportees coming from Greece have often been transferred to the Removal Centres of Kırklareli and Kayseri.

Initially, the centres of Harmandalı, Kırklareli, Gaziantep, Erzurum, Kayseri and Van (Kurubaş) were established as Reception and Accommodation Centres for applicants for international protection under EU funding. Following the EU-Turkey Action Plan on Migration of 29 November 2015 and the EU-Turkey statement of 18 March 2016, the centres re-purposed to serve as Removal Centres.

No access to asylum procedures

Several lawyers, human rights associations and migrants who were in contact with Deportation Monitoring Aegean pointed out that without a lawyer, it is practically impossible for a detainee to apply for any form of protection in Turkey from inside a Removal Centre.

The general legal frame in Turkey already drastically limits the ability to apply for asylum. Since Turkey has signed the 1951 Refugee Convention with a geographic limitation, only European citizen – meaning none of the deportees – can apply for asylum in Turkey. People from non-European nationalities can only be granted a weak Subsidiary Protection Status and for Syrians, the status of Temporary Protection has been introduced – a guest status that could be revoked anytime.

Even to apply for subsidiary protection is in practice impossible from inside the prison without a lawyer. Only very few detainees can access legal advice at all. Prisoners can only inform lawyers provided they have knowledge about this right, have language skills and a lawyer’s phone number. In addition, they require cash or a phone card for the prison pay phone since their own mobile phones will have been confiscated.

Harmandalı Remonal Centre, March 2019

Maltreatment and refoulement

Bar associations and several non-governmental organizations have been notified of severe rights violations of people held in the Removal Centre. These include violations to access to health services, ill-treatment, defamation, assault, lack of access to personal hygiene and hot water, widespread infectious skin diseases, inadequate nutrition, deprivation of privacy and the inability to exercise the right to petition. The situation inside the prison has led to several suicide attempts.

The Human Rights Association IHD also points out that the rooms are generally overcrowded. People who have – often arbitrarily – been branded as terrorists can be held in solitary detention. Typically, there is no information about the outside world, e.g. no radios or newspapers. According to IHD, detainees face arbitrary punishment when they do not follow prison rules, which are however neither written down nor explained to the detainees.

Detainees have to live under the constant fear of being deported. Many people eventually give up and agree to “voluntary return” to their countries of origin. Since the maximum duration of removal detention is 12 months, many people prefer to go back even to an unsafe country instead of remaining in highly precarious detention conditions for an entire year, after which they will probably be deported anyway.

Furthermore, lawyers and migrants reported to Deportation Monitoring Aegean that there have been several cases in which migrants signed voluntary return declarations in Turkish, because they were misled to believe it was a document needed to receive food in the Removal Centres. According to the interviewees, some migrants were simply forced to sign the declarations. Alternatively, prison guards signed the return declaration without consent on behalf of the detainee – a clear case of refoulement.

Threats and arrests of lawyers

Lawyers who provide legal aid in Removal Prisons reported having to face a variety of bureaucratic and practical barriers. They need to be able to present the correctly spelled name of a detainee in order to get access to the person. Accessibility is also difficult since it is not made transparent to which prisons people are transferred. In the Harmandalı Removal Center, lawyer’s bags are searched, they have to pass through an X-Ray device and they are closely guided by police officers. In some Removal Centres – especially Kayseri – lawyers have been denied entry based on alleged non-public rules or on grounds that their client is supposedly not there. They have no means to clarify whether the information about detainees given by the authorities in the Removal Centres is correct or not.

The Izmir Bar Association reports that furthermore, even if detainees have a lawyer, applications of lawyers and migrants are not registered, petitions are torn and written applications are not answered. In addition, lawyers trying to provide legal counselling face repressions by Turkish authorities: On May 14, 2019, eight lawyers and one interpreter from Izmir Bar Association were even arbitrarily detained for several hours within the Harmandalı Removal Centre.

The Izmir Bar Association explains:

“In essence, it is a systematic application aimed at concealing the rights violations of foreigners held at the center and preventing them from accessing asylum and attorney’s services. “

Statement by Izmir Bar Association, May 20th 2019

Protest before Harmandalı Removal Centre against the arbitrary arrest of lawyers, May 2019,

by Izmir Bar Association

Dramatic failure of the EU to evaluate and stop rights violations based on the EU-Turkey statement

The European Union did not only fund removal centres such as Harmandalı, but decided to consider Turkey a ‘safe third country’ within the frame of the EU-Turkey statement. The EU routinely returns migrants from the Greek islands back to Turkey based on the assumption that returnees can apply for protection in Turkey.

Deportations are ongoing despite the obvious lack of protection for migrants in Turkey who are directly detained and often deported to their countries of origin (see also Alpes et al., Ulusoy/Battjes). The European Commission simply ignores these facts and seemingly does not even monitor the treatment of migrants in Turkey anymore:

The European Commission already stopped to provide public reports on the implementation of the EU Turkey statement as early as September 2017. However, the last and Seventh report on progress in the implementation of the EU-Turkey statement leaves no doubts that people deported to Turkey have hardly any chances to be granted protection. The Commission stated on 6th of September 2017:

“So far 57 returned non-Syrians have submitted international protection applications to the Turkish authorities: two persons have been granted refugee status, 39 applications are pending, nine persons have received a negative decision. 831 persons have been returned to their countries of origin.”

European Commission (Highlighting added)

Deportation Ferry from Lesvos, entering the port of Dikili, Turkey

Furthermore, the Turkish state itself simply stopped producing statistics on the number and nature of decisions on asylum applications. The last available figures by the Turkish Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) are from 2016.

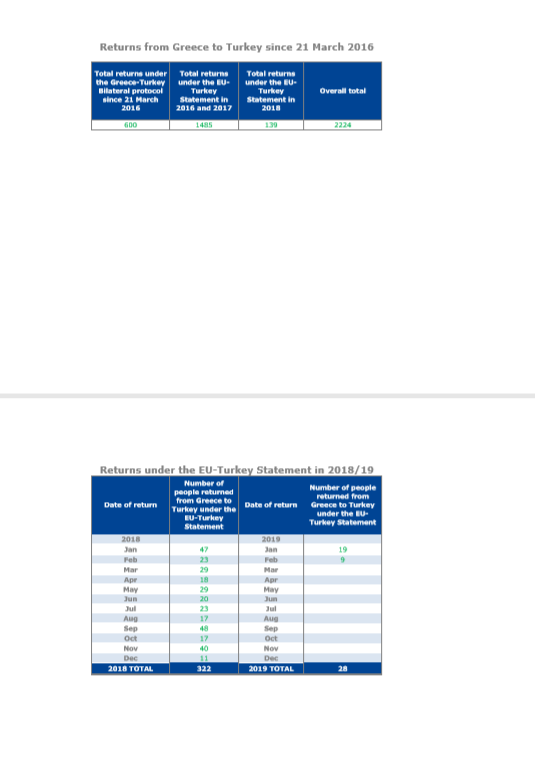

Despite this obvious lack of accountability, deportations to Turkey continue to be carried out and the European Union is turning a blind eye to the rights violations caused by its deportation policy. According to the UNHCR, from April 2016 until April 30th 2019, 1,852 people were deported from Greece to Turkey under the EU-Turkey statement. The Turkish DGMM reports about 1,861 readmissions from Greece since April 2016 until 27th of May 2019. The European Commission also counts the deportations from Greece to Turkey under a further bilateral agreement between Greece and Turkey leading to a number of 2,435 people from 22nd March 2016 until February 2019 (600 under the bilateral readmission protocol, 1,835 under the EU-Turkey statement). (The Commission even fails to correctly calculate the total number of deportations, mainly because the numbers from 2018 are not updated, which leads to the false presentation of an overall total of 2,224 people):

Screenshot taken on 3rd June 2019: Operational implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement (As of 12 March 2019)

The European Union’s externalization strategy and the deliberate ignorance of the post-deportation situation of migrants in Turkish prisons such as Harmandalı is shocking. It shows an entire lack of accountability and the European Commission’s priority to prevent migration and enforce deportations, regardless of the fact that this policy leads to the deprivation of the most basic rights of human beings.

V.H.