Deportation as a Business Model

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency, better known as Frontex, supports the operational implementation of the deportations under the EU-Turkey statement. This means that the agency is responsible for deploying so-called “forced-return escorts” that support the Greek authorities with deportations. Furthermore, Frontex supports the Greek authorities with technical assistance in terms of organizing means of transportation, operational coordination and financial resources of return operations. In a previous post we discussed the trajectory of deportation and illustrated how commercial tourist companies play a key role in facilitating deportations. In this post, we will elaborate on the collaboration between Frontex and commercial tourist companies to illustrate how commercial interest and migration management coalesce. In order to excavate this relationship, we will first shortly discuss the role of Frontex in the deportation process. After this brief introduction, we will discuss the relation between commercial companies and European agencies, to unpack the social and political implications of this cooperation. Yet, it should be mentioned that the role of Frontex within the deportation regime is complex, and the presented text is not an all-encompassing description of their tasks.

Frontex and “return” operations

Frontex was established in 2004 as a European agency for the management of operational cooperation at the external borders of the European Schengen area. The main mission of the agency was to support EU member states in implementing EU rules on external border controls and in coordinating cooperation between member states in external border management. In the wake of the long summer of migration 2015, the European Commission questioned the effectiveness of the agency. As a consequence, in 2016, the mandate of the agency was extended, through which the agency became a fully-fledged border and coast guard agency. According to the extended mandate, the role of the agency concerning “return operations” was expanded by allowing it to assist member states both operationally and technically. A Return Office was established that could deploy Return Intervention Teams composed of escorting and monitoring agents, and specialists dealing with related technical aspects of deportations.

Frontex supports the operational implementation of the deportations under the EU-Turkey statement. When the Greek authorities issue a readmission procedure, the Hellenic Police sends a request to Frontex for supporting and organizing the “readmission operation”. Frontex is responsible for deploying so-called Forced-Return Escorts, “an official of a competent national authority of a member state, who carries out escorting duties for the return of third country nationals” to support Greek return escorts during readmission procedures. As the name suggests, their task is to “escort” people, who are subject to a return decision, to be handed over to the third country authorities, in the case of EU-Turkey statement, the Turkish authorities.

Frontex return escorts always operate in the presence and under the supervision of Greek authorities. The Greek authorities are responsible for the readmission decisions and the legal procedures concerning the deportation, while Frontex seem to function as a deportation facilitator that cannot be legally held responsible for the legal procedure of the return decision. Because Frontex always operates in presence of Greek Return Escorts and Greek state officials, the agency clearly positions itself outside the legal procedures of the return decision and frames itself as facilitator. However, in fact, the agency facilitates arbitrary deportations that it should be held accountable for. Through our support work on Lesvos we witnessed how people with serious health issues and people who are still in their asylum procedure have been deported or how people still in their asylum procedure were listed people on a deportation list. As one of the main facilitators of deportations on Lesvos, Frontex expedite illegal practices. Moreover, the agency is an operational interlocutor and contributor on EU and third-country negotiations on returns, and has a high level of autonomy, and should therefore not be seen as merely a passive facilitator. Rather, Frontex is a high-ranking and influential player that actively engages within and shapes the EU-Turkey deportation regime.

Commercial Companies and Deportations

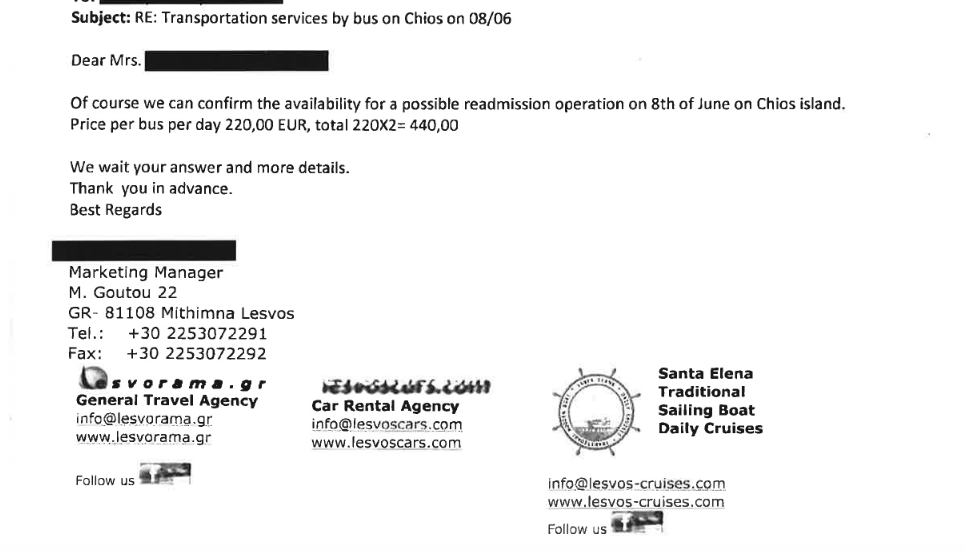

Frontex offers technical assistance in terms of organizing means of transportation, operational coordination and financial resources. Internal procurement documents and tender contracts show that Frontex signed several contracts with Greek tourist companies to “transport people by sea”. For example, in 2016 the travel company Lesvorama received a 127,300 EUR contract with Frontex to transport deportees by ferry (see email conversation Lesvorama and Frontex or awarded contracts 2016). Furthermore, Pantelopoulos Panagiotis, owner of PAN Tours Greece received two awarded contracts of respectively 42,470 EUR and 620,000 EUR to transport people by sea and by land (awarded contract).

Most recently, since the beginning of 2018, Frontex signed several contracts with commercial tourist companies to facilitate services that are needed “in support to law enforcement operational activities. The services are mainly associated with the corresponding transfers by sea between one designated port of departure in Greece and one designated port of arrival in Greece/Turkey” (Frontex tender contracts 2017).

- Pantelopoulos Panagiotis, owner of PAN Tours was awarded with a 1-million EUR contract to transport people from Chios to Cesme (Turkey).

- Sunrise Lines E.P.E. (Ltd) has a 2-million-euro contract to transport people from Lesvos to Dikili (Turkey).

- Samwell Limited was awarded with a 1-million-euro contract to transport people from Kos to Gulluk (Turkey).

The Costs of Deportation

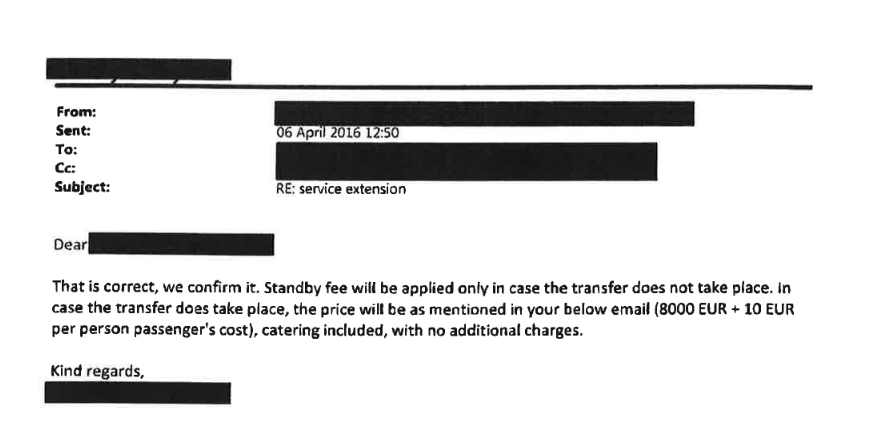

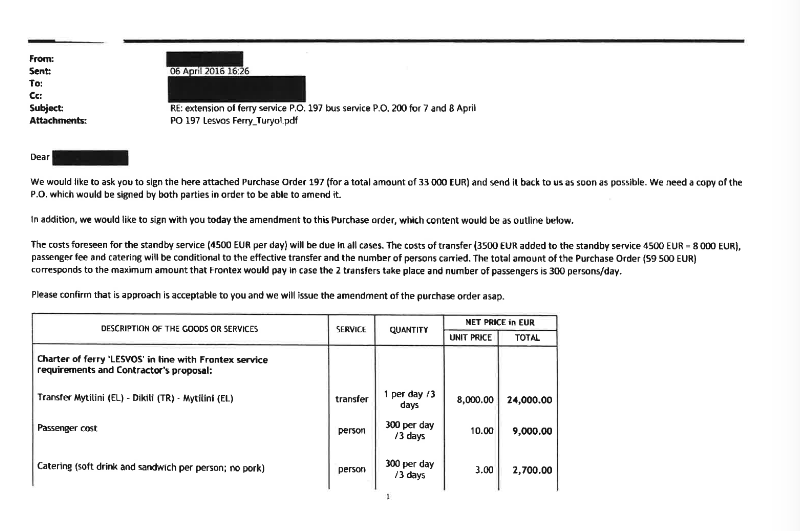

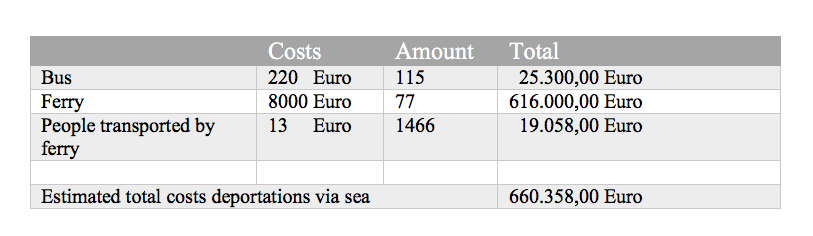

Frontex documents, requested under the Freedom of Information Act, show that between 2016 and 2018 (until 24.07.2018) Frontex chartered 77 ferry boats, 33 charter flights and 115 buses for deportations from the Greek Hotspots to Turkey. Although we have little information about the chartered flights, email correspondence between Frontex and the logistics companies gives an insight into the logistical costs of deportations to Turkey via sea. This email correspondence between Frontex and logistic industry is available online and shows the costs of renting one bus for one day in Chios and the costs of chartering a ferry from Lesvos to Dikili Turkey.

This email correspondence shows the costs of chartering a ferry from Mytilini to Dikili:

Deportation as a New Business Model

Given the above information we can have an insight in the costs of deportations under the EU-Turkey statement. In between 2016 and 2018 (24-7-2018) the logistical costs of ferry deportations can be estimated around 660.358,00 Euro. However, it must be noted that this is a rough calculation as most probably, many more financial resources are spent due to frequent cancellations of deportations, wages of Frontex personnel, transport from other Greek islands to removal centres, and so on.

Furthermore, we do not have any information about the costs of deportations by plane, which are most likely more expensive. Therefore the presented costs of deportation are actually much lower than the actual costs. Yet, the presented data exposes the enormous investment of energy and resourches to deport people who search for a better life. In other words, the EU-Turkey deportation regime operates with huge financial resources, thereby creating a new business model and financial incentive for private companies. This privatization of certain phases of the deportation process is a development we should continue to critically observe, because it could create another precedent to deregulate EUropean migration management. A precedent that could further collide migration management and human rights that further alienates the acountability of national and European authorities from their responsibilities in these processes.

Further reading about the dangers of privatizing migration management:

Privatization of Migrant Detention Centres

by P.