Since the EU-Turkey statement, migrants arriving from Turkey on the Greek Islands – on EU soil – are prohibited to travel freely within Greece. Their movement is restricted to the small Islands of Lesvos, Chios, Leros, Samos or Kos where the European hotspot camps are located. Some people have now been forced to stay in these ‘open air prisons’ for up to two years awaiting the decision on their asylum applications. Many migrants have no other possibility than to live in the so-called ‘European hotspot camps’ such as Moria camp on Lesvos Island during their entire asylum procedure. While the barbed wire appearance and the secured gates give the camps a prison-like appearance, the majority of migrants is able to freely pass the police secured entrances of the camp. After their full registration, asylum seekers are technically allowed to live outside the camp, which however is in practice hardly

ever possible, mainly due to limited housing opportunities and no possibility to pay rents.

Entrance of Moria Camp, Lesvos

Entrance of Moria Camp, Lesvos

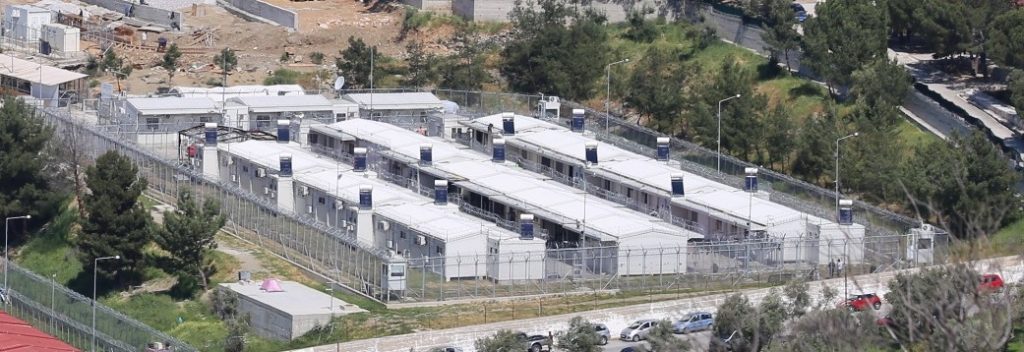

Some people are not only bound to stay on an island in a camp but are also held in detention facilities. On Lesvos for example, new arrivals are regularly detained on short term during their registration procedure in a special compound within Moria camp. Furthermore, Moria camp also features a prison, a so-called ‘pre-removal centre’ that is situated within the walls of the camp. It is a heavily secured area that currently holds around 200 people, with an official capacity to detain up to 420 people [AIDA]. The detainees are migrants, all of them men, most of them who came to Europe seeking international protection. They are held in a pre-removal centre that is divided in different sections, separating people based on their grounds of detention and their nationalities/ethnicities. Most of the time, the detainees are locked in containers and only allowed to enter the prison yard once or twice a day for one hour. Moreover, former detainees reported about a solitary detention room, where people can be held for disobedient behaviour for up to two weeks, sometimes even without light.

The pre-removal detention centre in Moria Camp

The pre-removal detention centre in Moria Camp

Legal Grounds for detention

Art. 46 of Law 4375/2016 (referring to Law 3907/2011 and transposing the EU Reception Directive 2016/0222 into national law) provides five grounds to detain migrants: 1) in order to determine his/her identity or nationality, 2) to “determine those elements on which the application for international protection is based which could not be obtained”, 3) in case “that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the applicant is making the application for international protection merely in order to delay or frustrate the enforcement of a return decision” (return decisions are in practice broadly issued to new arrivals and suspended or revoked for the duration of the asylum procedure), 4) if the person is considered as “a danger to national security or public order” or 5) to prevent the risk of absconding

[Law 4375/2016, art.46]. This variety of legal grounds for detention open the possibility to keep large numbers of people seeking international protection in detention facilities. Lawyers report that it is extremely difficult to legally challenge detention orders, among other things because the reasoning for the detention orders are very vague.

For asylum seekers, the duration of detention is generally limited to three months. However, it can be prolonged if e.g. criminal accusations are charged against them (that can for example arise after riots in the detention centre). The detention of migrants whose asylum application has been rejected or people who signed up for voluntary return can exceed three months. In some cases, people have to stay particularly long in detention and a state of limbo, when their asylum application and appeal is rejected but they cannot be deported because Turkey refuses to take them back. Lawyers can usually access the detention in the recommendation of the Asylum Service, however there is no individual reasoning for the detention. On Lesvos, apart from the involvement of a few individual lawyers, legal aid to challenge detention orders is almost non-existent which goes back to a lack of capacity and to systematic problems in the way courts address the “objections against detention”.

Detention in Practice – The pilot project targeting certain nationalities

Many people are detained in the pre-removal centre after their asylum claim has been rejected or declared as inadmissible and after they lost the appeal against this decision. Others are detained because they agreed to the so-called “voluntary return” to their country of origin with the International Organization of Migration (IOM) and are locked up while waiting for their transfer to another pre-removal centre on the mainland and eventually their deportation. Another highly problematic basis to detain asylum seekers is the classification as a danger to national security or public order. The police circular “Management of undocumented aliens in the Reception and Identification Centers (C.R.I.) – ASYLUM PROCEDURES – Implementation of Common Declaration of EU – Turkey of 18th March 2016 (realization of readmissions to Turkey)” exemplifies the practical side of this law. In the document, the wording “law-breaking conduct” or “offensive behaviour” („παραβατική συμπεριφορά“) is used as ground for detention. The police circular e.g. offers examples

for law-breaking conduct such as “thefts, threats-insults, body injuries [απειλές –εξύβρισεις], etc.”. Therefore, the classification of a person who committed minor offenses such as “trouble maker” and can thus be detained is left to police’s own discretion. Lawyers report that the paragraph is in practice often used to detain people who trespass the imposed geographic limitations.

First page of the police circular from June 2016

Furthermore, the possibility to detain people based on the assumptions that they are applying for asylum to avoid or hamper the preparation of the return or removal process is widely used as justification of detention. In actual practice, the detention order often depends on the pre-assumed chances of an asylum seeker to be granted a protection status, which is again related to the asylum seeker’s national belonging. In fact, this leads to the automatic detention of male migrants from certain national backgrounds immediately after arrival. While the European Commission frequently recommends the extension of detention of migrants in order to facilitate returns, the specific detention based on nationality goes back to a so-called pilot project that is reflected in the above mentioned Greek local police circular from June 2016. In this document, the Ministry of Interior describes migrants from Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka sweepingly as ‘undesirable aliens’ with an ‘economic profile’, whose data are to be collected not only in the Schengen Information System but also in a Greek database called ‘State Catalogue for Undesirable Aliens’ (EKANA). This pilot project had two phases and was eventually extended to target all people whose acceptance rate for asylum – measured by nationality – is statistically less than 25%. This applies to many people from African countries and was formerly also used for Syrians. (Syrians used to have a high rejection rate because their asylum claim was often declared as inadmissible since Turkey is considered as safe country for Syrians.)

This arbitrary process strongly contradicts the Genève Convention’s notion to provide individuals with the rights of an impartial and individualized examination of their asylum claim. Moreover, it creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: Under the conditions of detention, asylum seekers have less access to legal counseling and are under strong pressure. In many cases they have only 1-2 days to prepare for their asylum interview and are unable to inform the lawyers about their upcoming asylum interview, because they are prioritized in the procedures. These factors are significantly lowering their chances to present their asylum claims well in the asylum interviews in order to be granted international protection status.

While in detention, they are in many cases handcuffed during their registration and asylum interviews – thus stigmatising them as dangerous and suggesting potential danger to both the asylum seeker and the first reception/asylum service. An individual e.g. reported that being handcuffed while being questioned left him unable to speak a single word during his registration, where it would have been crucial to clearly express the will to claim asylum.

The rationality behind the detention of asylum seekers with low recognition rates seems to be aimed at rejecting and deporting them within the three months of detention – which so far has not even been achieved in most of the cases. Instead, this mostly leads to a mechanical procedure of unjustified detention. People from nationalities such as Algeria and Cameroon are detained directly on arrival and simply condemned to wait for their three months of detention to expire and to be set free afterwards. Once they are released, they find themselves in the overcrowded camp Moria, without any sleeping place or sleeping bag, and full of insecurity as to where to find orientation in an environment that treated them not as humans seeking protection but as criminals.

Police is guarding the Moria pre-removal centre at the entrance

Police is guarding the Moria pre-removal centre at the entrance

Conditions of detention

Within the pre-removal centre, the detainees lack basic goods such as sufficient clothes and hygiene products. Apart from two days per week, their phones are confiscated. Visits can only be carried out by close relatives and – in case they are lucky enough to have one – by lawyers and two persons working for a state owned health company. Despite their presence, many of the detainees reported serious mental and physical health problems. In some cases, sick people are transferred to the local hospital but this depends on the discretionary decision of the police and their capacity to escort them. Several detainees described problems like strong head pain, insomnia, panic attacks and flashbacks similar to symptoms of e.g. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Some detainees inflict themselves self-harm through heavily cutting their bodies and some have tried to commit suicide. While people who are classified as vulnerable are not supposed to be detained, there were several cases where vulnerability was only recognized after weeks or months of detention or only after their

release. Some people released from the pre-removal prison reported that they are survivors of torture and imprisonment – often the reason why they fled to Europe in the first place to seek safety only to find themselves again in prison. Medical examinations showed that some individuals detained in the pre-removal centre were minors. Although they had repeatedly expressed that they were under age, they were kept for many more weeks until the age assessment was finalized. Other people are held in detention, although they speak rare languages such as Krio, for which no translation is available and hence no asylum interview can be conducted.

The barbed wire of Moria Pre-removal detention centre

The barbed wire of Moria Pre-removal detention centre

The stories of Individuals in Moria pre-removal centre

In the following, some accounts recently given by migrants about their detention in Moria’s pre-removal centre are illustrated in order to highlight the impact of the detention regime on individual fates. A young man from Cameroon was detained in the Moria pre-removal centre directly upon arrival under the so-called pilot project. He reported that he had tried to commit suicide on the night of the 7th to the 8th of September but was prevented from doing so by his friend. He had been detained since end of June 2018. He complained about insomnia and strong anxieties connected to experiences in the past, including the death of his brother and the fear that also his child and the child‘s mother might be dead. He postponed the date of his asylum interview four times, because he felt mentally unable to carry out the interview.

A 22-year-old individual from Syria who arrived on Lesvos with serious back problems was detained in the Moria pre-removal centre after he had signed up for ‘voluntary return’. In Turkey he had had a surgery following an accident, leaving him with screws in his back. He decided to return to Turkey, because he found that the necessary surgery to remove the screws again could only be done there. On July 18 th , he reported having been severely beaten by a police official in the detention centre of Moria Camp. On the same day, independent volunteers handed in a complaint to the Greek ombuds-office. He was visited in detention by an ombudsperson on July 20 th and asked if he would hand in an official complaint but he refused fearing the consequences. Only four days later, on July 24 th, the man was deported.

A man from Pakistan was detained on April 18 th on Kos Island after the rejection of the appeal against the first-instance rejection of his asylum claim. A few months later, he was transferred to the pre-removal centre in Moria camp on Lesvos Island. The authorities aimed to deport him to Turkey, but the country did not accept him back. The man reported that he was regularly throwing up blood and still sufferes from a heart attack he had had a year ago. According to his account, he was promised by the authorities to be brought to hospital on September 10th . However, he was instead transferred to the pre-removal centre Amygdaleza close to Athens on September 9 th where he is now awaiting his deportation to Pakistan.Another individual from Algeria remains in pre-removal detention, although he suffers from major psychological problems and is frequently strongly self-harming through severely cutting his body.

Four young individuals who claim to be Afghan nationals but were classified as Pakistanis in the screening by FRONTEX were detained although they reported to be minors. One of them had been detained on the mainland in the pre-removal centre Alledopon Petrou Ralli and was transferred to the pre-removal centre on Lesvos Island after one month. He was then forced stay there for another few months, before finally being officially recognized as minor through an age assessment and released together with another individual who was also recognized to be under age. One of the individuals was considered an adult after the age assessment and the result for the fourth person is still pending.

The deportation of an Algerian national who was detained in the pre-removal centre on Lesvos was halted at the last minute through the involvement of UNHCR. He was supposed to be deported back to Turkey on August 2 nd only six hours after the second rejection of his asylum claim, leaving him unable to challenge the decision before the judicial instances throug a so-called application for annulment. He was brought to the deportation ferry and only removed again at the last minute because the UNHCR pointed out that he did not get the chance to exhaust his legal remedies in Greece and that he might get a vulnerability status. However, considering the lack of lawyers on Lesvos and the costs and work

load of an application for annulment, he was finally unable to object the deportation and was deported only two weeks later, on August 16th.

The impact of the detention policy

The extensive use of new legal possibilities to detain migrants has reached a new quality at the EU external border in the Aegean. The freedom of movement is gradually restricted. Thousands of people are forced to stay in the transit zone of Lesvos Island for long periods of time, and most of them have no other choice than to live in the European hotspot camp Moria. Others are even detained within the pre-removal detention centre located in the camp. There is increasing pressure from EU-level to impose detention measures. Also the Greek law, eventually based on the EU Reception Directive, provides enhanced possibilities to keep migrants in detention. In the practical implementation, they are extensively used predominantly for male migrants. More than to facilitate returns – that are comparatively low in numbers – the detention measures carry out a profound disciplinary function. They create strong insecurity and fear.

Especially the practice of being detained immediately upon arrival sends the strong message to the affected person, as it is expressed in the police circular: You are an ‘unwanted alien’. This is a pre-decided stigma although the asylum procedure has not even started and the reasons as to why a person came to the island are unknown. Affected people reported that they feel treated like criminals. In many cases, they do not understand the procedural grounds for their detention and are therefore exposed to even stronger stress.

Especially those people who have already been arbitrarily detained in their home countries and on the flight routes report about flashbacks and psychological problems arising from the conditions of detention that can lead to a re-traumatization.

Even if they are eventually released, they are still in a mental state of detainability and deportability – the constant fear that they could be arrested and deported anytime, without any legal options to defend themselves. These policies of detention of migrants are not intended to solve the problems of the so-called ‘refugee-crisis’. Instead, they aim with limited success to ensure that the EU-Turkey statement functions and that at least some returns of migrants to Turkey can be carried out. On a local scale, the detention policies are furthermore primarily measures of oppression, designed to be able to prevent riots and supposedly to “handle” a situation that is in fact “unhandable”: the concentration of

thousands of people – many of them who suffer from psychological illnesses such as traumatization – for months and years in highly precarious living conditions on an island where people slowly lose all hope to find a better future.

By V.H.

The pre-removal detention centre photographed from the outside of Moria Camp

The pre-removal detention centre photographed from the outside of Moria Camp