“Please help us, we are locked up in a prison here, you can’t imagine how it looks like. There are concrete walls and barbed wire fences. We are in a cage beside some forest; everyone is really scared. I don’t understand this. I only want to understand why we are sitting in this prison. No one tells us anything and the police treat us like shit, we are suffering here. They only call us by numbers, no names. When a friend tried to take pictures of the camp with his phone, the policemen took his phone and just destroyed it. There is one policeman who is not as bad as the others. He told us that they destroy the phones because this camp here is not allowed. Why can we not wait outside with the other people here? We are coming for asylum, we are not criminals, we did not do anything, we only want a better life and to be safe.”

Tarik (name changed) from Palestine, February 2020

Prison Camp Pyli on Kos

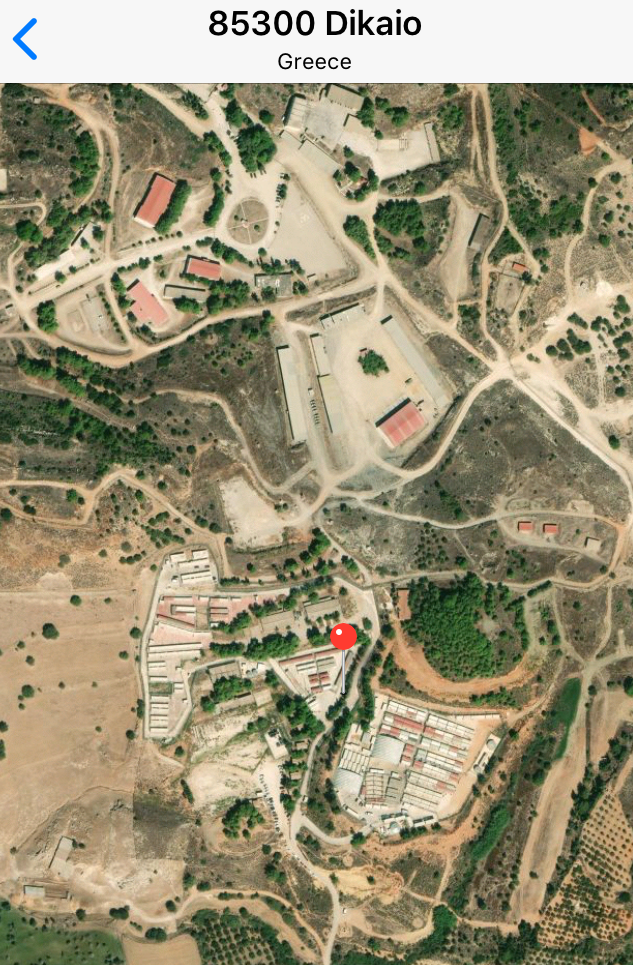

Tarik is one of approximately 200 people arrested and detained on the Greek Island of Kos. Detained with him are people from all different nationalities (African, Asian and Middle Eastern countries), among them families with small children. The closed camp surrounded by barbed wire is divided in different sections named from Alpha to Zeta, some for single men, some for families. It is located in the area of Dikaio, right beside the open European Hotspot camp in the village of Pyli.

The people inside are detained for one reason only; they reached Kos by boat in an attempt to apply for asylum in the EU. Since the right-wing ‘Nea Dimokratia’ government came to power in Greece, everything has been done to carry out as many deportations as possible. In January 2020, the government introduced a new extremely restrictive asylum law and began to sweepingly arrest and detain all new arriving migrants, no matter whom.

The people detained inside report their fears. They hardly get any information about their situation and their main contact is with police guards who are unable to explain anything about the asylum procedure. Some detainees have also reported severe incidents of police violence inside the camp, e.g. when a Syrian man was beaten unconscious after attempting to take photos of the camp with his phone. It seems that UNHCR is permitted to enter the prison camp with limited capacity but is not speaking out about the detention situation.

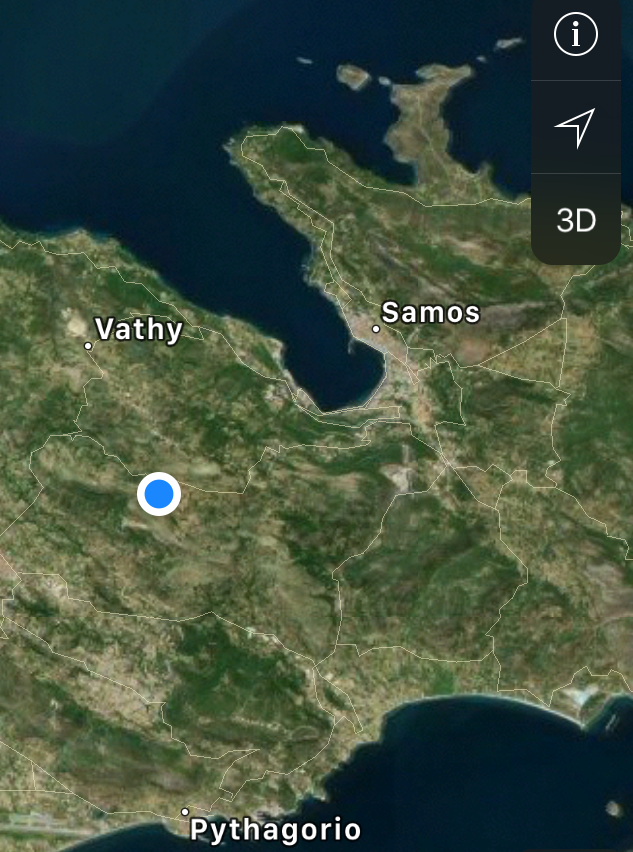

The Location of Pyli Detention Centre.

Satellite Image of the Detention Complex on Kos.

From time to time, people are taken out of the prison to be deported. Recently, without comment from the authorities, nearly everyone inside the prison was handed out deportation papers written in Greek, which provoked an enormous fear amongst the detainees. It has already occurred under the new government that asylum seekers have been rejected without any asylum procedure. The detainees were not informed that the deportation decision is suspended until the end of the asylum procedure. Many other worrying stories have been shared, shedding light on an asylum system lacking sufficient accountability. For some people, the intention to apply for asylum seemingly has not been registered; Syrians seem to be sweepingly rejected on inadmissibility grounds, and some report that they were called liars during their interviews; others have stated that they have no chance to appeal their negative decision because they physically cannot access legal aid or the asylum service.

Incarceration on the other EU Hotspot Islands

While the extend of detention policies is most severe in Kos, migrants seeking protection have for a long time been incarcerated within the other European hotspot islands in the Aegean. In the hotspot Moria, single male asylum seekers coming from countries with low recognition rates for asylum are systematically detained upon arrival, while some women are detained in the police stations of the towns of Mytilene (there is also one family detained), Kallonis-Antissas and Gera because they are accused of breaking geographic restrictions. Also on Chios and in other islands, migrants are held in police stations.

Plans to build closed camps have been announced several times by the Nea Dimokratia government. Although the EU rejected to finance those closed camps, on 10th of February the plans were confirmed again by the government. On Lesvos, the camp should be build in the West in Karavas, on Chios in the area Cretan Lakos, on Samos in Zervos, on Leros in the area Lepida. In the last announcement it was stated that detainees would be allowed to exit the camps during the day for a limited time regulated by a card system. The current examples show that this is not the case but instead people are incarcerated.

However, at least on Lesvos it seems to be practically impossible to lock down and control 20,000 people currently living in Moria camp, who are regularly protesting for their freedom in big marches. So far, no construction work of a closed camp has started on Lesvos island. However, as we see on Lesvos, already the current strategy involves incarcerating selected new arrivals, prioritizing their interviews and rejecting them within a few days, therefore swiftly deporting them and preventing them from exhausting their legal remedies – while simultaneously pushing the interview dates of former arrivals back in the queue, keeping them in limbo in the abandoned precarious camp situation.

On Samos, the new closed camp is already under construcion. There has never been a pre-removal centre in the hotspot camp Vathy. But now, there is a new camp being built in the vast mountain area Zervoy – far away from the overcrowded hotspot camp near the town of Vathy. While the construction site was initially started in order to build a new open camp, following the announcements of the Greek government, it will most probably also become a prison camp for migrants.

It is unclear how the situation will continue to develop. Increasing the number of deportations will not be possible without severe rights violations such as arbitrary detention and procedural rights violations. While the Nea Dimokratia government has proven to wilfully accept this, the EU seems to quietly watch the situation that it created deteriorate at a neck-breaking speed. However, one thing is for sure, migrants will continue to fight for their rights. Incarcerating people for exercising their legal right to apply for asylum will not happen in a vacuum and will not go unchallenged. We will see more demonstrations soon; no matter how much violence the police use to violently oppress them.

V.H.