By M.E.

He could have died at any other moment during the journey. He could have died trying to cross from Turkey to Greece, after being attacked by Greek coastguards, or after being abandoned on a life raft without engine. He could have died in the prison inside Moria camp, trying to end the suffering of being locked up in hell for no reason. He could have died in a container, running out of oxygen, trying to get out of Greece.

On his way to Europe, it could have been in any of the death traps set to kill those who dare to dream of a safe place to live. Many other lives have been buried in the mass graves of Fortress Europe. Dead in a war that becomes more shameless and warlike every day.

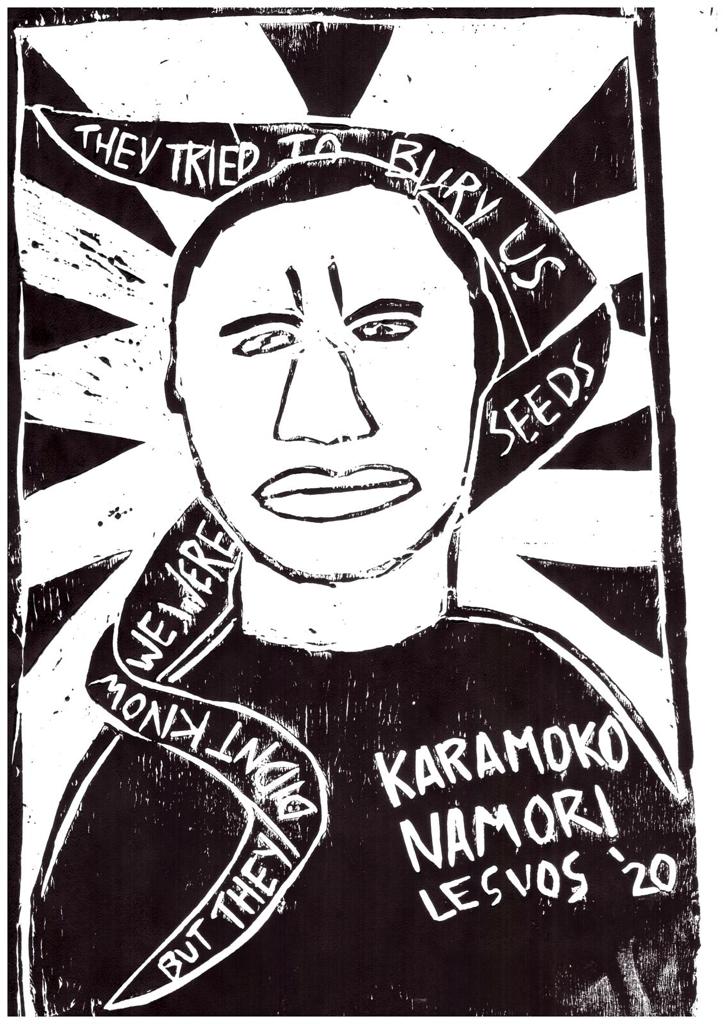

Today he is dead. His body buried somewhere. His name on a list in the hospital with some notes and marks to differentiate him from the rest, because it was his turn to die. In the roulette game of death and despair to which people on the move are subjected, it was his turn to be unlucky. His nationality and age will be recorded in a short article in the local press.

On the night of 5 July, a fight broke out over the theft of a telephone in Moria refugee camp (Lesbos, Greece). A large number of people were injured by knives. Many of them had to be hospitalized. Karamoko Namory, 19, born in Ivory Coast, died after being stabbed. His comrades see this as another instance in a long chain of injustices striking at their Black bodies:

We escaped the violence in our (looted) countries to find a safe place. They locked us up for three months in a hellish prison when we arrived in Greece without explaining why. When we get out of hell they kill us. There is no reason for so much pain.

There is no reason for so much pain.

There is no reason for so much pain.

Sometimes we think there is a reason for everything. Sometimes we need to understand the reasons for pain, suffering and death.

Perhaps understanding the reasons allows us to stop it from happening. Transforming pain into a political tool. Perhaps not. Maybe it just allows us to store it in a way that hurts less.

Karamoko Namory was stabbed in the night of 5th July 2020 in Moria refugee camp. He was in his tent, near one of the camp’s WIFI hotspots, a place frequented by the small armed groups who steal telephones. The country of origin of these people is usually Afghanistan. This information is just as irrelevant as it is crucial. After a phone was stolen, a fight broke out between people of Afghan origin and members of the African communities. Karamoko came out of his tent to see what was going on, and was stabbed in the chest. Now his name is on a list with some notes and marks to differentiate him from the rest, because it was his turn to die in this game of roulette.

Some friends sent messages that night saying, “the fight is still going on, the police haven’t intervened yet” and “the police have come and gone soon after”. Later, “we went to the police for protection, but they chased us and beat us”. Some Black comrades pointed out that the police reaction was the result of racism. “They are racist towards Black people.”

There is no denying that the police enjoy witnessing Black bodies being injured and murdered. It is also true that violence in the Moria camp in certain ways benefits the authorities in the camp, and legitimizes the very existence of these death camps.

Not only did the police and those responsible for the camp fail to protect the life of Karamoko. It was not an accident. The clear impunity under which these groups operate shows that there is no will to end the insecurity in the camp. If there were, they could quickly put an end to the activity of these groups, identifying them (if they do not already know them) in less than 24 hours. The question is whether this lack of willingness is simple neglect or a deliberate decision. Especially because maintaining impunity for these criminal groups allows authorities to focus attention on the conflict between communities and maintain a climate of terror that facilitates control of the camp.

In this twisted logic, when “a group of men born in Afghanistan steal and kill”, the conclusion is that “Afghans are murderers”. This fuels internal racism, and conflict between communities puts the spotlight on differences between people on the move and reduces the chances of communities to work together and resist collectively.

The impunity of these groups also keeps the population of the camp terrorised and paralysed, in a state of permanent insecurity. This is one more thread in the web of tortures endured by people on the move. One comrade wrote: “I am Karamoko”. Tomorrow it could be you. Thousands of people who fear every movement, who cannot sleep. Exhausted and terrified. Months ago a woman said, “How can we organize and resist? How can we think clearly? We are sick and exhausted.”

If the authorities in the camp maintain impunity for these groups for their own benefit, they are responsible for Karamoko’s death. Responsible as much, or more than, the knife.

But responsibility for this murder goes beyond the camp. The tangle of fighting, gun violence and murder also feeds the racist imagery of the “other”, the “violent and criminal savages.” A discourse that seeks to dehumanize people on the move in order to justify the war being waged against them. A discourse that seeks to justify in the social imaginary how more than 20,000 people can live in physically and psychologically inhuman conditions. This racist discourse is not exclusive to extreme right-wing groups, but is also among those who supposedly work in solidarity with migrants. Following a fight that resulted in the stabbing of a Greek person a few months ago, a well-known NGO shamelessly wrote the following, addressing “all refugees” in a supposedly civilizing lesson:

But, as we try to show people that you suffer in your own countries, and that we have to leave racism behind, you show the face of racism between you. And you fight with your own people and you kill each other, in the country you came to ask help from. How then, can people trust you, and support you, if they are afraid they might be the next victim?

…

When we disagree on something, we sit down and talk. We use knives to cut our bread and food, sat together around a family table to eat.

And actually they are right. Most Europeans use knives to cut bread, because they do not dirty their hands with blood when they kill. We sit at the family table, while maintaining these camps where people are crowded together without any rights. That “father of the family who cuts bread with the knife” is one of the coastguards responsible for the murder a few weeks ago of four people who were trying to reach Lesbos from Turkey. For example. The fathers of the family are the businessmen, politicians, policemen and all those who directly or indirectly participate in this Europe that long ago learned to steal and murder in a subtle and silent way. All the people whose silence makes them accomplice.

The false notion of civilized Europe seeks to hide its colonial and violent past, its neo-colonial and violent present. A Europe that has been historically nourished by the exploitation of “everything else”, in a process of capital accumulation through dispossession and plunder. A historical reality that at the same time explains why millions of people are forced to leave the territories where they were born to end up in a refugee camp like this one. Maintaining this discourse of “civilized Europe” versus “violent and murderous migrants” is especially important today, given that the explicit violence on European borders and the clear retreat of the rights of migrants is clearer than ever and must be legitimized.

In war the enemy is not human.

I would like to say that Karamoko was not killed by a knife, nor by a person from Afghanistan. Not only. Karamoko was killed by a system that uses and disregards the lives of migrants. Karamoko was killed by a camp where people are tortured, and where the lives of all those who live there are sacrificed for a higher purpose. Keep the walls of Europe high, the mass graves full. To keep the plundered treasure in their hands. Karamoko represents the way in which the historical genocide on which Europe was built and is maintained today

Perhaps it is useful to remember, so as not to be blinded by the glare of the knife, the spectacle prepared to distract our attention, the theatre of death ready to continue its silent murders. To say that the police, the state, the European Union and its racist states are responsible for Karamoko’s murder would allow us to understand that we can only get out of this when we identify the real murderers. The murderers beyond the knife.